Addressing hot takes about scientific research done on music

I’m always interested in ‘hot takes’ on micro-blogging platforms that take issues with scientific research done on music. See here for previous thinking on the topic.

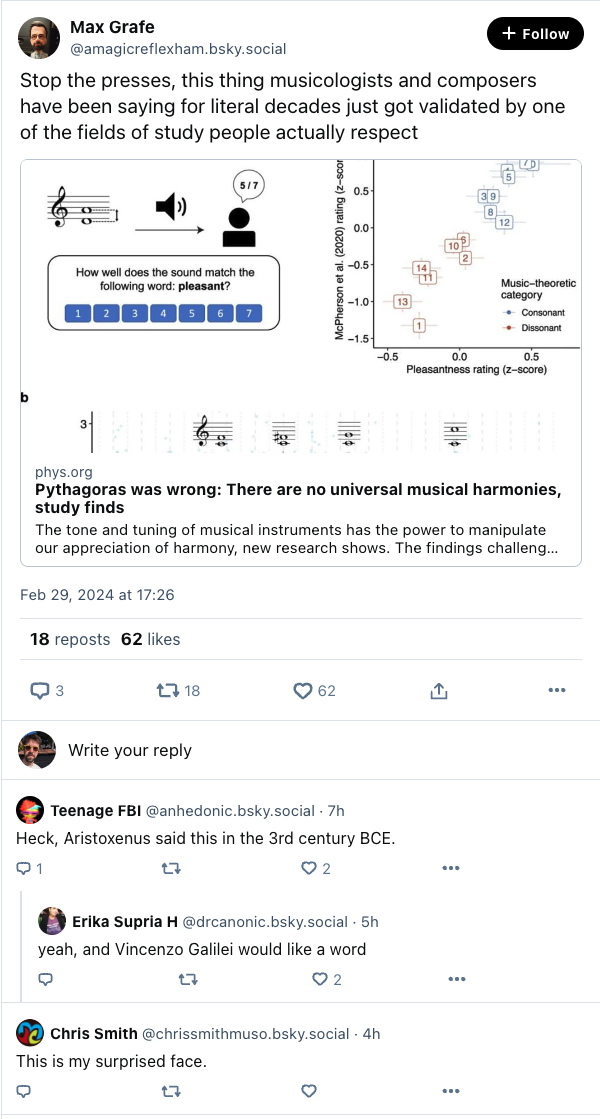

On my last day of work in the Music Cognition Group I came across this tweet on my BlueSky feed.

Seeing tweets like this is half the reason why I log on to platforms like this, but what more caught my attention was Max’s response to Bryn clarifying his grievance.

Of course while I was writing this post, Peter chimed in and the two clarified the issue, but given that I see the “why do we test stuff we already know” trope pretty often, maybe it’s worth explicitly addressing this common concern for those who don’t work in the sciences.

I was able to think of three things worth mentioning.

We’ve known about this for a long time

First, let’s address the “musicologists and composers have been saying [some sort of idea] for [very long time]” sentiment. This is often true and of course should be the basis for any scientific research on music. As the authors of the paper in question reference in the first paragraph of their article, there has been a lot written on the topic.

So much has been written on the topic that there is bound to be ideas that all vary in their degree of how correct they are. No idea will be 100% true, no idea will be 100% false. There will be situations where something is true under one set of assumptions, but not true under others.

The problem is that since composers and musicologists have said so much on the topics, which should we accept as the basis for our understanding of reality going forward? It’s quite convenient to be able to say when something empirically works out, say we knew this all along, and mock all the bad ideas that we can clearly see in retrospect. But before doing this kind of empirical work, we only have case study examples that are chosen to overfit to specific examples and must expand out this to know exactly how far the idea extends.

But how precise?

Second, even if we did have a list of all the mostly correct ideas from the musicology, theory, and composition literature, most of these ideas or theories are grossly under specified. For those who have had the opportunity to dive deep and read all these primary and secondary sources, it’s possible to get a good idea of what these authors meant. But often when you want to apply the tools of the sciences to any ideas (music or not), there is almost always a giant gap between the idea as expressed in text and a clear enough formalization of the concept that it can be cleary understood, without question so it can be understood within the context of a scientific theory.

The point of building computational models is to formalize and clean up our thinking in such a way that (to borrow my favorite quote from the above linked paper) “your ideas will run on someone else’s computer” (A.G. Wills, quoted here). The beauty of computational models is that you have a clear starting place for the discussion and can avoid these SMT style back-and-forths where someone says something akin to “Yes, but what do you MEAN by HARMONY”.

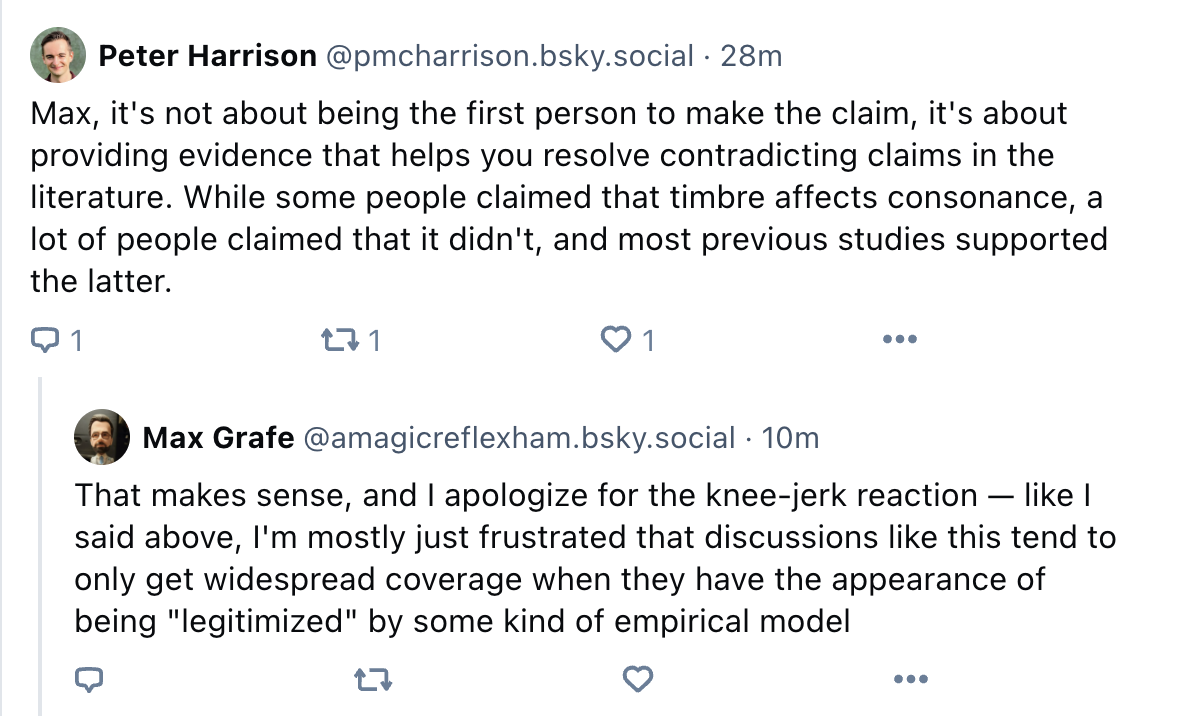

A great example of this is Peter and Marcus’s paper on consonance perception. The brief summary of it is that there are of course many competing ideas of what causes something to be perceived as consonant or dissonant. The big contenders were interference, periodicity/harmonicity, and cultural familiarity. Related to this idea of ideas being underspecified is just how many different instatiations of “things musicologists and composers have been saying for ages” can be constructed to describe the same thing (See the paper’s Figure 1). It takes time and care to formalize these ideas to the point that they can be compared in the boring and tedious way that lets us better understand how this phenomena links to other things we know.

It shouldn’t always have to be groundbreaking

Lastly, of course studies like these might not be as surprising or exciting for those working in music for those who are not as interested beyond high level descriptions, but I think it’s also worth mentioning that I don’t think it’s fair or good for science and empirical work in general for us to demand that every paper is some sort of ground-breaking, new, radical insight that changes our thinking.

Both people from the sciences and humanities should propose big ideas, based on our intuition of the world, then the fun and joy of doing research is trying to take that idea apart, see what’s essential, what’s redundant, and find ways that we can make our thinking clearer.

I get the sentiment that the sciences are stealing the thunder (a big focus of this other blog from a few years ago) of more ‘traditional’ music research. This is such a problem that many people without science training in music fields will sometimes borrow (sorry to be sassy with this next one) the budget version of some idea or tool from the sciences, then –without accepting the responsibility that comes with using these methods– we can end up with music research that sort of looks like science to the scientifically untrained, but in reality is just the worst of both worlds.

This is of course also bad. It’s important for the two cultures to keep one another in check. Some people think the best way to do this is collaboration, which I largely agree with. But I will take a more controversial opinion and also say that I sometimes think that too much collaboration can lead to an abdication of responsibility at times. Just as “music” people get upset when the “science” people don’t get it entirely right and expect them to have engaged more deeply with a subject they know well, it’s important to remember this is a two way street.