Invasion of the 'Non-Musicians'

At the end of last week Ted Gioia shared a blog post that reminded him of “the STEM-ification of musicology and how desperately we need more interdisciplinary dialogue about music”. In the post, Gioia makes the point that people with STEM backgrounds are, to use his word, “encroaching” on music studies. This inevitable encroachment is made even more harrowing by his chosen key quote which reads:

“STEM researchers have access to much more grant money than any musicologist can even dream of. If scientists want to take over music scholarship, no one will stop them.”

For those who regularly work in the interdisciplinary space, this might sound very familiar as it is something David Huron has also predicted about the future of music studies.

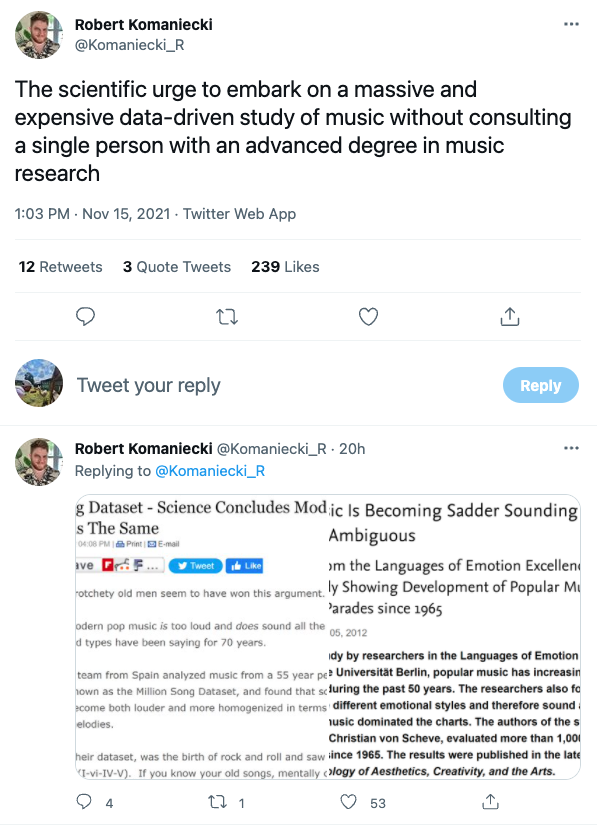

Since writing my first draft of this post, one of the music theory meme pages has also carried a darker form of that energy into this week.

This mostly has come in the form of gate-keeping and degree shaming, two things I thought we were trying to distance ourselves from as music scholars.

As well as making some quite, what I felt to be very rude, comments about some of the empirical literature that the author had the luxury of deleting.

Both the Gioia blog, as well as some of these other tweets, could generously be read to just be calls for more interdisciplinary dialogue (can’t argue with that), but the more I thought about them, the more something just didn’t sit well with me about the encroaching language and the meme page. And this sentiment clearly resonates with a lot of people who follow these music meme pages, the tweet got many likes.

I’ll engage with Ted’s blog so I can do a bit of thinking out loud regarding what didn’t sit well with me. I don’t really have time to re-write this to be more tweet-centric, but I think most people will see those connections.

In talking about his own reading in the past 30 years (which, I assume means the majority of his professional career?), the author says that most of what influences him comes from “outside of music academia”. Fields that have influenced him include:

- Neuroscience

- Evolutionary Biology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Mythology

- Folklore

- Sociology

- Anthropology

- Cultural History.

Here a presumably clean line is drawn between music and not music. But is making this demarcation really that simple? If we assume for a second that maybe it is true and that pure music research can be excised from other disciplines, does it also then follow that only music researchers are equipped to deal with new research that might involve music?

What felt strange in continuing to read this article, thinking about these questions about disciplinary boundaries, was the lurking assumption that scholars with professional training from other fields are somehow ill equipped to be asking the types of questions that they find interesting about music because they don’t have a formal music background.

The examples that are used to illustrate the “splintering of knowledge” are where I am directing my attention when it comes to this. I’ll quote it at length since there is a lot I want to reference directly.

But the absence of a significant, ongoing dialogue between music scholars and these other disciplines is regrettable. Perhaps neuroscientists, for example, are overreaching and reductionist in their attempts to ‘explain’ music—but no matter what your views on that topic, the efficacy and value of their research will be improved if musicologists engage with them in constructive dialogue. And the same is probably true of many STEM fields that are now ‘encroaching’ on music studies—just wait and see what damage will be wrought by algorithms and artificial intelligence. Nothing in the music world today will have more impact than these expert systems, created by well-meaning outsiders who will completely change our musical culture, often without actually understanding it.

This trend won’t end any time soon—if only because STEM researchers have access to much more grant money than any musicologist can even dream of. If scientists want to take over music scholarship, no one will stop them. They will even get a blank check and a comfy corner office to help them do their work.

OK. A lot to think about here. I’ll comment on a few small things, then hopefully loop back around.

Neuroscience

First is the neuroscience anecdote, noting the possible “overreaching and reductionist” attempts to explain music. This presumably is attributed to the fact that a neuroscientist might not have received “adequate” formal music training, thus are more likely to over-generalise their results. This to me feels like a strawman.

Any ‘overreaching’ when it comes to the (neuro)science literature is usually some journalist trying to cajole some scientist into packaging their finding into a punchy headline to fulfill their impact requirements. Scientists almost pathologically avoid making any substantial claims about what their findings do and do not imply.

It’s interesting that the meme page references two news articles covering the two academic articles and not the actual articles themselves. And also suggested another blog post that seems to do the same thing (reference a journalist’s version of the article rather than read the author at their words).

You can read that article here.

The thing is, claims of being too ‘reductionist’ when it comes to science more broadly, to me at least, feel like it’s more the critic finding an novel way to show off how little they know about what is needed to do in order to run a well-designed experiment than providing the searing take down they think it is. Science is almost by definition reductionist. The world is very, very complicated and it needs to be made simple if you hope to gain even modicum of understanding of the part you are trying to tack down. Also, confusing the small world of statistical models with the “real” world is something you learn early on in many science classes.

Even stranger is the belief that introducing someone with a (historical?) musicology background will be able to join a team of neuroscientists, look at their experimental design and statistical analysis, and then tell them a better way interpret their results. Usually what happens in these types of collaborations is that those without any scientific training will, yes of course, suggest things that might make it more ecologically valid or realistic, but with those changes also always comes the possibility of more confounding.

I have seen it happen where the stimuli used were a bit naive or confounded, but it happens. If you know exactly how things are going to turn out, you’re not really doing science are you? You fix it, move on, and learn something. Sometimes it is very bad and destructive, especially in “universality” literature, but that’s another conversation and not what is being referenced here.

And even though this runs counter to a deeper point I want to make, it is not like the people who want to invest all the time and resources required to run an fMRI experiment are not “musicians”. Many of these people have had tons of experience actively practicing and making music. But even if they didn’t, I don’t think that it should preclude people from pursing questions dealing with music and musical behavior. These arguments smell like what is used to discredit non-traditional forms of music making entering the music conservatory space.

What should preclude you is to go head first into an area and declare that you are starting a new science of music, conveniently not engaging with the decades of scholarship on specific topics that has existed. If you are going to do interdisciplinary work, you really do have to read a lot.

AI

A similar scenario is put forward in the blog post with the case of AI. Yes, AI used inappropriately will be bad. There is already overwhelming evidence about this in many situations.

But again, the issues at the intersection of AI and ethics and music don’t just need any old music humanities person to be pushed on to their team to prevent the havoc. They need a team of people, all who read about this very new, important, large, very relevant area to discuss these problems.

And to assume that these STEM people need to work with people in music to prevent this damage happening weirdly just lets the STEM people believe that the ethics of developing new technology can just be passed to other people. They can just focus on “the science”. (ha!)

I guess the point I am trying to make here is that it’s not just about bringing experts together from disparate, enshrined silos of academia to work together. It’s about acknowledging that what we study changes fast and we all miss out if we draw a line between where one discipline starts and another ends. It’s about providing the awareness and access way earlier in our training programs so that we don’t trick students into thinking that there are clear boundaries.

The other major issue of one discipline encroaching on another also, again, to me at least, feels like one discipline is coming for another one’s questions. This is of course a bit more difficult to disentangle because what has been thought of as “music” research and “science” research have historically been more intertwined.

But in a more contemporary sense, music researchers and science researchers are often interested in very different kinds of questions. They also adopt very different epistomological and ontological assumptions about the subject of their research. This might be the real issue that generates this rift. And to assume that there is only one, and that one is traditionally music’s point-of-view, feels like it is committing the exact sin of saying science is being too monolithic.

Or maybe it’s humanities music researcher’s fear that the public will be unquestioning in their reading of any scientific literature. This is also a real concern, but feels like the enemy here is scienceism, not the literature that has been referenced, is the problem.

It is not as if there is core, finite, and bounded set of “music” questions (and assumed shared epistomological point-of-view) that is still in need of being “discovered” and that by adding Science to it, somehow this makes it better or more efficient (Feyerabend’s Cosmology A, p. 198). Often I feel that if you take the questions of those who work in music departments and then add Science without thinking critically, this almost inevitably makes the research worse.

It should be also noted that not all musicologist’s questions of interest are even made better with the tools of science. Having science tacked on to an argument in many ways detracts from the larger point being made.

Then lastly, before I try to summerise things neatly, I also want to return to this idea of if the study of music can be excised out and neatly partitioned. One of my first thoughts when looking at the list above was actually wondering what this argument would look like if someone said that most of the new and interesting findings about music were actually coming from disciplines outside of music, but then listed areas such as queer, colonial, Indigenous, or gender studies?

Are those subjects not music? Some cranky old men would probably say so. It almost feels like there is a shadow version of that blog post that could be written that takes that point of view. And were we to not allow ideas from gender studies, neuroscience, biology, queer studies, psychology , mythology , Indigenous studies, sociology, anthropology, colonial studies and cultural theory to inform how we think about music, what would be left with?

So what are my major points now that I have thought out loud about this?

The first is STEM people are probably qualified to be asking the questions they want to ask of music. Yes, having more disciplines contributing to any question would be better, but that feels like it is true of almost any research endeavour. A lot of the ‘Non-musicians’ are probably actually very well trained in what they do, but that really shouldn’t matter. If we want to have diverse questions being asked about music, we should not insist that the only people who can ask them are those that share our background.

Second, just because you have traditional music training, it doesn’t follow that you’ll be automatically helpful on other projects. An advanced degree in music does not guarantee this and you are setting people up for failure if you tell them this. What is needed is to actually read the articles (not what other people say about them) that have been written and ask questions when you don’t understand. We should work to provide as much infrastructure as possible to help people pursue the questions they find interesting and expose people to many different methods, questions, and epistomologies as we can during training.

So, yes, maybe the tweet version of this blog is “yeah, more interdisciplinary dialogue!”, but it’s way more interesting than that.